Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL)

What is Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL)?

A diagnosis of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is overwhelming, and you may have many questions about the disease and its treatment. Your doctor and health care team are the best resources for helping you learn more about APL. This guide is designed to provide information that supports what your doctor has already told you and that helps you think about what additional topics you’d like to discuss with your doctor.

APL is a subtype of acute myelogenous (or myeloid) leukemia (AML), one of four types of leukemia. Leukemias are known as hematologic cancers (or hematologic malignancies) because they affect blood cells. AML is defined as acute because it develops and progresses quickly, in contrast to a chronic leukemia, which progresses more slowly. AML is myelogenous (or myeloid) because it begins in the bone marrow, the spongy center inside of bones. Bone marrow is where blood cells are made.

AML is not a common cancer. APL is even less common. The risk of AML is higher for older people, but the APL subtype occurs more often in people who are younger than 65 years of age.

To better understand APL, it is helpful to first learn about how AML develops.

Development of AML

All blood cells begin as stem cells in one of either two lines of blood cells: lymphoid or myeloid. In people with healthy blood production, both lymphoid and myeloid stem cells mature and become distinct kinds of blood cells. Lymphoid stem cells develop into white blood cells (lymphocytes), and myeloid stem cells develop into red cells, white cells (myelocytes), and platelets. Each kind of blood cell has important functions in the body. With AML, there is uncontrolled proliferation (growth) of immature white blood cells, or myeloblasts. This uncontrolled growth causes an excess accumulation of malignant myeloblasts (also known as leukemia cells), similar to how cancer cells accumulate to form a tumor in other types of cancer (for example, in the breast or colon). However, with AML and other hematologic cancers, the collection of leukemia cells does not form a tumor. Instead, the accumulation of leukemia cells results in fewer healthy blood cells for two reasons: the leukemia cells do not become healthy blood cells and as they increase in number, they crowd out healthy blood cells. The decrease in healthy blood cells can lead to:

- Anemia, caused by a low number of red blood cells

- Reduced ability of the body to fight infection, caused by a low number of white blood cells

- Problems with blood clotting, caused by a low number of platelets

- Leukemia cells can leave the bone marrow, enter the bloodstream, and travel throughout the body, affecting orther organs

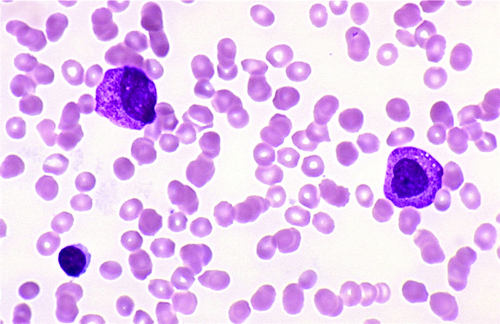

Malignant Promyelocytes

Image courtesy of Kristine Krafts, MD

Classification of AML

While most cancers are staged according to the extent of disease and the prognosis (likelihood of cure), hematologic cancers are classified according to morphology, or the appearance of the leukemia cells when they are examined with use of a microscope. AML is classified according to the French-American-British (FAB) system into eight subtypes, referred to as M0 through M7, according to morphology and how mature the leukemia cells are at the time of diagnosis. With advances in technology, researchers DNA structure of the leukemia cells is another important factor in classifying AML. These changes are known as chromosomal changes or cytogenetic changes. Determining the subtype of AML is important because the type of treatment and the prognosis vary according to subtype.

APL is classified as AML subtype M3 in the FAB system. In the WHO system, which is genetic based, APL is classified as APL with t(15;17)(q22;q12); PML-RAR?. APL gets its name from the stage at which the leukemia cells stopped maturing. Th ecytogenetic changes in APL occur in chromosomes 15 and 17. See Diagnosis for more information on the APL subtype and these cytogenetic changes.

The severity of disease at the time of diagnosis varies among people with APL. In some cases, APL begins abruptly with bleeding complications that must be treated immediately. These complications can be serious if not identified and treated as soon as possible. For this reason, treatment is usually started immediately even if APL is suspected but not yet confirmed. Once the results of more sophisticated diagnostic testing become available, treatment can be modified, if necessary.

This content provides an overview of the diagnosis of APL to help you better understand the importance of molecular testing, a more precise method for determining the response to treatment than traditional methods. The majority of the content focuses on the treatment of APL, with an emphasis on the importance of monitoring for evidence of molecular response. Also discussed are complications that may be associated with APL and its treatment, as well as measures to prevent and control these complications.

APL is a complex disease, and it can be challenging to understand it because of many unfamiliar and complicated terms and concepts. Terms are defined at the end of articles, not only to help you as you read this content but also to help you recognize terms used by your doctor and other members of your health care team. You are encouraged to talk to your health care team about anything you don’t understand and to ask questions to help you better prepare for treatment and recovery (below).

| Definitions of Terms | |

| Acute myelogenous (myeloid) leukemia | A cancer of blood cells that develops in the bone marrow; it has a rapid onset and progresses quickly |

| Anemia | Condition caused by a low number of red blood cells; may cause fatigue, pale color of the skin, and shortness of breath |

| Bone marrow | Spongy center inside of bones, where blood cells are made |

| Cytogenetic | Related to the study of chromosomes |

| Morphology | Study of the form and structure of cells, especially the cell appearance and how the characteristics of abnormal cells compare with those of healthy cells |

| Myeloblasts | Immature white blood cells in the bone marrow (also referred to as blasts or leukemia cells); malignant myeloblasts accumulate in leukemia |

| Red blood cells | Carry oxygen throughout the body |

| Platelets | Blood cells that prevent bleeding and form plugs (clots) that help stop bleeding after an injury |

| Proliferation | Continuous development of cells |

| Stem cells | The type of cell from which blood cells originate; lymphoid stem cells develop into white blood cells (lymphocytes), and myeloid stem cells develop into red cells, white cells (myelocytes), and platelets |

| White blood cells | Fight infection in the body; there are two major types of white blood cells: germ-eating cells (neutrophils and monocytes) and lymphocytes |

Questions to Ask Your Doctor

- How much experience do you have treating this type of cancer?

- Should I get a second opinion?

- What treatment choices do I have?

- Are there other tests that need to be done before we can decide on treatment?

- Which treatment do you recommend, and why?

- What are the risks and side effects to the treatments that you recommend?

- Should we consider a stem cell transplant? When?

- What should I do to be ready for treatment?

- How long will treatment last? What will it involve? Where will it be done?

- How will treatment affect my daily activities?

- Are there any specific factors that might affect my prognosis?

- What is the outlook for my survival?

- What would we do if the treatment doesn’t work or if APL recurs (comes back)?

- What type of follow-up will I need after treatment?