Myelofibrosis

Introduction

Learning you have myelofibrosis is often unsettling and unexpected. To better understand this rare blood cancer and make informed treatment decisions, it is important to learn as much as you can. As you do your research, you will find that doctors are learning more about the genetics behind the disease, finding new ways to treat it and developing better ways to address side effects that typically go along with it.

The Basics of Myelofibrosis

Myelofibrosis is one of six myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). These cancers affect the bone marrow in different ways:

- Essential thrombocythemia (ET) — too many platelets

- Polycythemia vera (PV) — too many red blood cells

- Primary myelofibrosis — too many fibroblasts

- Chronic neutrophilic leukemia — too many blood stem cells become a type of white blood cell called neutrophils

- Chronic eosinophilic leukemia — too many of the eosinophil white blood cells in the bone marrow

- Chronic myelogenous leukemia — too many white blood cells are made in the bone marrow

When myelofibrosis develops from ET or PV, it is known as secondary myelofibrosis, which may also be referred to as either post-ET myelofibrosis or post-PV myelofibrosis. When it develops spontaneously, it is known as primary myelofibrosis. Although myelofibrosis is considered a chronic (slow-growing) blood cancer, in some cases it can transform into acute (fast-growing) myeloid leukemia.

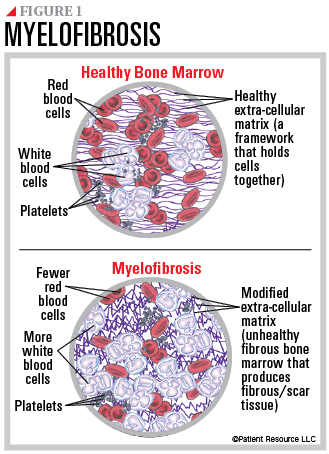

Myelofibrosis starts in the bone marrow, which is the soft, spongy center of some bones. It is where blood is created and is made up of blood stem cells, more mature blood-forming cells, fat cells and supporting tissues. Blood stem cells can become one of the following:

- Red blood cells that carry oxygen from the lungs to other parts of the body

- White blood cells that fight off infection and other foreign intruders in the body

- Platelets that help blood to clot and to stop bleeding

This cancer begins when abnormal blood stem cells produce immature cells that grow quickly and take over, crowding out other cells. This affects the development of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets. They are often misshapen and immature so they cannot perform their normal function. As a result, there are low levels of red blood cells and too many white blood cells (see Figure 1).

When not enough normal blood cells can be made, blood cell production may shift to other organs, such as the spleen or liver, which causes them to enlarge. For example, when the spleen tries to compensate for the lack of blood cells, it enlarges and often presses against other organs.

Myelofibrosis symptoms, progression and treatment can vary widely. Most common symptoms are fatigue, feeling full quickly, weight loss, fever, bone pain, night sweats, itching (especially after bathing), and abdominal discomfort or bloating. In the absence of symptoms, blood tests may indicate abnormal amounts of cells that can prompt the need for further testing.