Prostate Cancer Survivor

Knowing the score: Cal Ripken, Jr. talks early detection & hope for the future

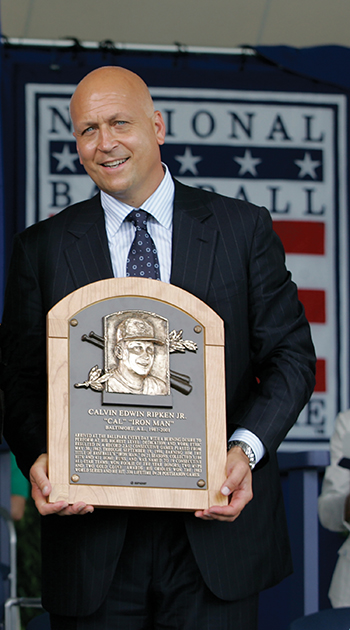

Baseball Hall of Famer Cal Ripken, Jr. went public with his prostate cancer diagnosis to encourage men to get their annual physicals. Early detection gave the former Baltimore Orioles shortstop more treatment options. As a result, he is cancer-free and feels great.

Cal Ripken, Jr. has been in the spotlight for most of his life. He grew up around the game watching his father Cal Ripken, Sr., a former minor league player, coach and manager who went on to manage the Baltimore Orioles. Now as a retired Hall of Fame player himself, Cal and his brother Bill have carried on their dad’s legacy of helping underserved kids fulfill their dreams by giving them opportunities in baseball and much more through the Cal Ripken, Sr. Foundation (RipkenFoundation.org). They’ve just completed building their 100th Youth Development Park and are currently helping more than 1.5 million kids make smart and healthy life decisions. The Foundation has exceeded their wildest dreams. And though Cal is comfortable being in the spotlight for the organization, going public with a very personal prostate cancer diagnosis wasn’t his original plan.

“Honestly, my first inclination was to not tell anyone,” he admitted. “I didn’t want anyone to feel sorry for me or look at me different. Then I realized how lucky I was to have been diagnosed early. It made all the difference for me, and I don’t think men are aware of how much worse it can be if you don’t find prostate cancer until it is advanced.”

Cal wasn’t experiencing symptoms when his cancer was discovered. He was having monthly bloodwork done to find a cholesterol medicine that worked for him. His doctor always included a PSA test with the bloodwork. When he noticed consistent increases in Cal’s PSA level, he referred Cal to a urologist.

“The urologist ran tests that would indicate if a biopsy was necessary, and it was. While I waited for the results, I rationalized what could have caused my rising PSA level. I biked daily and thought perhaps the pressure from the bike seat could be the cause. But when the urologist asked me to come in for the biopsy results instead of delivering them over the phone, I knew it couldn’t be good news.”

Cal was shocked to learn he had early-stage prostate cancer.

“As soon as I heard the word ‘cancer,’ I tuned out,” he admitted. “Everything the doctor said sounded like the teacher in the Charlie Brown cartoons. Fortunately, my wife Laura was with me. She took notes and asked questions then filled me in later when we got home. She continued to go with me to all the appointments.”

Cal was completely confident in his urologist’s expertise, and he relied on him to recommend a treatment plan.

“My urologist was on it. He is a researcher, and he explored the options that would be best for a guy my age,” he explained. “I was considered young – 59 – and we both wanted the results that would allow me to keep the functionality that was important to me.”

He laid out different options to Cal and recommended surgery to remove his prostate. He added that the cancer appeared to be slow-growing, so Cal could take some time to learn about and consider his options.

Laura weighed in with her opinion.

“She was concerned, but she always approaches things very sensibly. She encouraged me to get the surgery and get it quickly. Why leave something growing in my body when I could take care of it right away?”

According to Cal, timing also played a role. It was the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and hospitals were beginning to make decisions about the surgeries that could and couldn’t happen.

“There is a lot to learn when you have a decision like this to make. After taking Laura’s thoughts and everything else into consideration, it wasn’t difficult. I called on a Tuesday and had the surgery on that Friday.”

He checked in to the hospital around 4 a.m. and was in recovery by 7 a.m.

“Nerve damage can cause incontinence and affect sexual function, and that was obviously a concern. The last thing I said to my doctor before I went into surgery was to make sure those nerves weren’t affected. He told me he couldn’t promise anything and would know more once he got in there. As I recall,” Cal laughed, “that was also my first question once I woke up.”

The surgery was successful, and Cal was released under the care of his doctor early that same evening. Pathology results later showed the cancer was completely encapsulated within the prostate gland, and he was considered cancer-free.

“I continue to have regular bloodwork, but the follow-up checkups are becoming farther apart.”

As he moved into survivorship, Cal reconsidered keeping his diagnosis to himself.

“All along, I truly felt that I was going to be fine,” he explained, “and I thought about how I could help someone else feel confident making the same important decisions. I decided to open up about my experience to let others know there is hope with a prostate cancer diagnosis.”

He chose to focus on early detection, encouraging men to get tested by making and keeping their annual physicals.

“As a professional baseball player, I’d get a complete medical workup every Spring Training. Once I retired, it became more of a challenge. I’d get busy, and all of a sudden I’d realize I hadn’t been to the doctor all year. Finally, I got myself on a schedule that coincided with Spring Training because that was an easy thing for me to remember.

“Laura’s opinion on what to tell men was, ‘Just listen to your wives.’ That’s pretty good advice because men – me included – tend to be pretty stubborn about going to the doctor. Women seem more apt to stick to a schedule for medical appointments. In fact,” he went on, “when we moved from Baltimore to Annapolis, Laura pushed me to find a doctor in town. I’m glad she did. The doctor I found was aggressive in detecting my prostate cancer. The change in my PSA score from year to year could easily have been written off as normal for a man my age, but because he ran the tests monthly, he was able to see the incremental changes in my PSA score and he didn’t like the movement. I am thankful for that.”

Cal understands that making an appointment for a physical is one hurdle, but another is doing something about it if a problem is found.

“I’ve heard that when some men are told they need a biopsy, they walk right past the scheduling desk and never come back. I get that the thought of having a biopsy may make some men cringe. For me,” he admitted, “the biopsy was not a big deal, and definitely not worthy of passing up the chance to catch prostate cancer early. It gave me options.”

After sharing his story with the media, Cal was surprised at how many friends and acquaintances made appointments to get checked out.

“I’ve been stopped going into the grocery store and hardware store by people thanking me for talking about my diagnosis. Some men share their stories with me, and some simply thank me for being open about it. A lot of my former teammates were tested, and many asked questions. I gave honest answers, and I hope that gave them confidence.

“Years ago, a cancer diagnosis was a death sentence. My dad died at 63 from lung cancer. With all the advancements made in prostate cancer, there is hope — especially when you catch it early. Make an appointment, gather your information and then take action.”

Elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2007.

Elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2007. A comprehensive and engaging STEM program is part of the Cal Ripken, Sr. Foundation.

A comprehensive and engaging STEM program is part of the Cal Ripken, Sr. Foundation. One of the 100 Ripken Foundation Youth Development Parks.

One of the 100 Ripken Foundation Youth Development Parks.