Sarcoma

Treatment

Treatment advances in the past two decades, particularly in targeted therapy as well as limb-sparing surgical procedures, have led to better outcomes for people diagnosed with sarcoma. The availability of more treatments for both soft tissue and bone sarcoma means many people are able to live longer, better quality lives either disease-free or progression-free.

You are encouraged to seek care from a sarcoma specialist or at a dedicated sarcoma center. If that isn’t possible, talk to your medical care team about reaching out to a sarcoma center for advice and planning, as most are happy to offer help.

Your medical team will recommend a treatment plan based on the type, stage and location of your sarcoma, as well as your overall health and other factors. It’s important to talk with your doctor about all treatment options that may be available to you. Typically, a combination of treatments offers the best approach. Clinical trials should also be considered and may be of particular benefit for treating rare sarcomas.

Surgery

For both soft tissue and bone sarcomas, a primary treatment is surgery. The most common surgical procedure used is wide local excision, which removes the entire tumor as well as a close margin of normal tissue surrounding it. Another name for this procedure is Wide en bloc Resection, which means removal of the entire tumor in one piece with a cuff of normal tissue surrounding it to ensure complete removal of every malignant cell without contamination of surrounding parts.

A pathologist (a doctor specializing in diagnosing disease) examines the margins under a microscope to check for cancer cells. If no cells remain, the margin is clean (also called negative or clear), and no further treatment is necessary. But if cancer cells are present (positive margin), then another surgery, radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy may be needed. The surgeon and pathologist work closely together to determine the adequacy of the margins.

Advances in surgical technologies and other treatment options have greatly reduced the number of amputations performed when sarcoma occurs in the arms or legs. Surgeons today prefer a limb-sparing procedure whenever possible to preserve the use and appearance of the limb. To replace tissue or bone lost in the limb from removing the tumor, bone or skin is grafted from elsewhere in the body. Radiation therapy may follow.

Amputation is not used as often as it once was, but it may be the best option if removing the tumor would also require removing essential nerves, muscles or blood vessels that would result in a poorly functioning or nonfunctional limb. Amputation may also be considered if the surgical area cannot fully be covered with soft tissue or the person cannot undergo reconstructive surgery.

In the likelihood that the sarcoma has spread to nearby lymph nodes, the surgeon will remove and examine them to check for cancer cells in a procedure called a lymphadenectomy.

In some cases of bone cancer, cryosurgery (also called cryotherapy) may be an option. Cryosurgery differs greatly from traditional surgery. Instead of removing the tumor through an incision, the surgeon inserts a hollow instrument through the skin into the tumor to deliver extremely cold liquid nitrogen (or argon gas) to kill sarcoma cells.

Chemotherapy

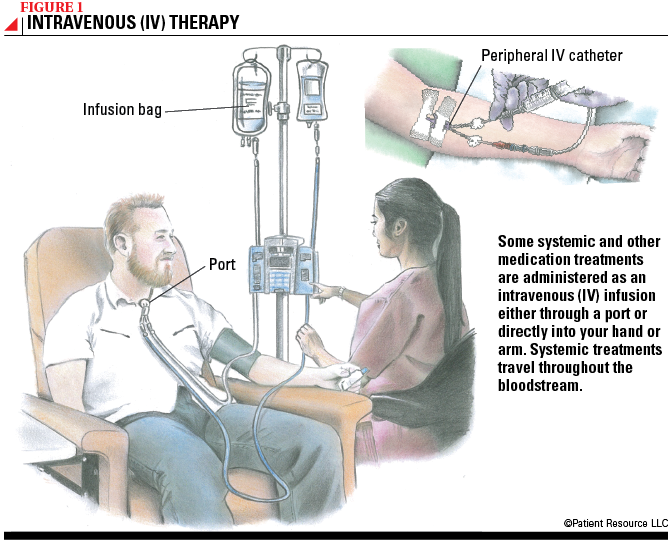

Chemotherapy involves using drugs to stop cancer by either killing cancer cells or preventing them from dividing and growing. It may be given orally (a pill) or intravenously through a small tube inserted into a vein (see Figure 1).

It may be given before or after the primary treatment, which is typically surgery or radiation therapy. Chemoradiation, a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, may also be used. If surgery is not possible, chemotherapy may be used as a primary treatment. Because chemotherapy is systemic, which means the drugs travel throughout the entire body in the bloodstream, it may be used when the sarcoma has metastasized to several sites.

Chemotherapy is primarily used to treat Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, embryonal or alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in children or young adults, and sarcomas that have spread. When used for bone sarcomas, it is usually given before and after surgery. Several chemotherapy drugs can be used to treat sarcomas, alone or in combination with other drugs.

| Common Chemotherapy Medications |

| dacarbazine (DTIC) |

| dactinomycin (Cosmegen) |

| doxorubicin (Adriamycin) |

| eribulin mesylate (Halaven) |

| tazemetostat (Tazverik) |

| trabectedin (Yondelis) |

| vinblastine (Velban) |

| vincristine |

| Combination treatment: MAID (mesna, doxorubicin, ifosfamide and dacarbazine) |

Targeted Therapy

This approach uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific types of cancer cells. Effective targeted therapy depends on two factors: identifying targets essential to cancer cell growth and survival, and developing agents to attack those targets. For example, a type of targeted therapy pinpoints gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) cells with a specific gene abnormality that is found in the majority of GISTs. The targeted therapy drug helps prevent recurrence after the tumor is removed. Molecular testing will determine if the GIST has this gene abnormality. This strategy may also be used as primary treatment for GISTs that cannot be surgically removed or that have spread. If the initial drug used stops working, other targeted drugs are available.

Another type of targeted therapy is a monoclonal antibody that binds to a kind of protein (RANK ligand) to prevent it from telling specific cells (osteoclasts) to break down bone. This drug helps shrink giant cell tumors of bone that have returned after surgery or that can’t be surgically removed.

Targeted therapy may be a treatment option for sarcomas that are resistant to chemotherapy.

Considered a systemic treatment because the drugs travel in the bloodstream throughout the body, it typically doesn’t damage healthy cells, which may result in fewer side effects. Targeted therapy may be given in pill form or intravenously through a small tube inserted into a vein (see Figure 1, above). Because healthy cells are usually spared, fewer side effects may occur.

| Common Targeted Therapy Medications |

| denosumab (Xgeva) |

| imatinib (Gleevec) |

| olaratumab (Lartruvo) |

| pazopanib (Votrient) |

| regorafenib (Stivarga) |

| sunitinib (Sutent) |

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses the body’s own immune system to slow the growth of or kill cancer cells, much in the same way the immune system fights off bacteria or viruses. A category of immunotherapy drugs called cytokines is sometimes used to treat certain sarcomas. The drug works by delivering large amounts of laboratory-made cytokines into the immune system to promote specific immune responses.

Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating the effectiveness of other types of immunotherapy to treat sarcoma.

| Common Immunotherapy Medications |

| interferon alfa 2-b (Intron A) |

| interleukin-12 |

Radiation Therapy

.png)

Radiation therapy uses high-energy X-rays or other particles to kill cancer cells or prevent their growth. With this kind of therapy, treatment is carefully planned and overseen by a specially trained doctor called a radiation oncologist.

Newer radiation therapy techniques allow doctors to direct radiation more precisely. This means higher doses of radiation can be delivered while avoiding damage to healthy tissue, which may reduce side effects. Research has demonstrated lower rates of cancer recurrence with these newer radiation techniques.

The most common type of radiation therapy used for soft tissue sarcoma is external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) (see Figure 2). Other types of radiation therapy also may be used (see Table 1). For osteosarcoma, radiation therapy is usually used only for tumors that cannot be surgically removed.

Radiation therapy may be integrated into the overall treatment plan in several ways.

- Before surgery, to shrink the tumor and make it easier to remove. This is known as neoadjuvant treatment.

- Following surgery, to kill cancer cells near the tumor site. This is known as adjuvant treatment.

- Instead of surgery as the primary treatment for a tumor that cannot be removed surgically or when the person cannot tolerate surgery because of health conditions.

- To help relieve symptoms from sarcoma that has metastasized (spread) to other parts of the body.

Table 1. Types of Radiation Therapy Used for Soft Tissue Sarcoma

| Type of Radiation Therapy | Description |

| Brachytherapy | Radiation is delivered via radioactive “seeds” implanted near the tumor. |

| External-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) |

Delivered from a machine outside the body, these types of radiation therapy are strong enough to kill cancer cells:

|

| Intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) | A single, powerful dose of radiation is delivered during surgery once the sarcoma has been removed. |

Palliative Care

Palliative care is designed to relieve pain, distress and other physical and emotional side effects of cancer and its treatment and, in turn, improve quality of life. Often confused with hospice care, which helps enhance quality of life for people approaching the end of life, palliative care focuses on people whose illnesses are life-threatening or chronic. This includes people experiencing symptoms from sarcoma or its treatment. It is provided by a multidisciplinary team of doctors, nurses, social workers and others.

For people with sarcoma, palliative care may involve drugs to manage pain or nausea, radiation therapy to help relieve bone pain or chemotherapy to help shrink a tumor causing pressure or a blockage. It is available from the time you’re diagnosed throughout the duration of your treatment, so don’t hesitate to discuss it with your doctor.

Follow-Up Care

Sarcoma that returns after treatment is called recurrent cancer. To monitor for a recurrence, follow-up visits are generally recommended every four months for the first two to three years, with longer intervals after that. Your doctor will establish a schedule for you. Depending on the type of sarcoma, your appointment may include a physical exam, blood tests, bone scan and imaging studies, such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound.